This is a translation of a short intervention I was invited to contribute to Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft. You can read the original German text here.

To discuss large language models (LLMs) in the “Tools” section of the Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft is already to take a stand. After all, the debate about whether LLMs are tools or agents is far from settled. The latter position does not even have to mean the fantasies of artificial general intelligence that OpenAI boss Sam Altman posits as the ultimate goal of any technical development. It might be enough to regard LLMs as partners in an “artificial communication” that are sufficiently unpredictable to create the “double contingency” of communicative behavior. And research on the “scene of writing” (Schreibszene), abandoning the idea that texts are necessarily produced by humans, should also be able to warm to the reverse assumption that machines could be a “subject of writing” or participate in it.1

That I still treat large language models as tools is simply due to the fact that they are still primarily used as such at the moment. Two aspects of this tool-like nature deserve highlighting, even in the most abbreviated manner: how they facilitate reading and how they facilitate writing.

The Facilitation of Reading

The first is located even before the text is produced, which is usually regarded as the actual product of the writing process. This is evident in translation services such as DeepL or language transcription services like Otter.ai. An as yet much less discussed function seems to be the facilitation of reading, namely by summarizing what has already been written. If I ask Claude to reduce an essay to its basic arguments, I can get an idea of whether it is worth taking the time. Such ‘synoptability’ seems to be closely tied to textual genres and disciplinary boundaries. Empirical social science articles, computer science white papers, even overlong encyclopedia entries can often be summarized sufficiently well. By contrast, a Lacan seminar, everyday communication based on things left unspoken as well as most kinds of poetry can rarely be reduced in a way that preserves what is not purely propositional to them. Those who write obscurely, one might say, will still not be read in the future – not only not by humans, but also not by machines. But this is hardly the fault of LLMs. Like all tools, they cannot be applied to just any domain, even if they, used as a hammer, make everything look like a nail.

But where the digital humanities want to grapple with the great unread at a distance, the rest of the humanities may now indulge in the promise that machine learning will now also provide an overview at close range—or, as Arno Schmidt once sighed, make the divergence between life-time and reading-time a little less steep.2 All this means is that AI offers a solution to a problem for which it is itself responsible. If, as Matthew Kirschenbaum has stated, large language models cause a “textpocalypse” and flood the web and our lives with synthetic writing, then they also provide the means by which this flood can be controlled again: through summaries and textual condensations. 3

This is remarkable in two ways. First, the summary as a means of reading becomes a means of writing again, namely when authors have their abstracts generated. Secondly, when I have a text summarized by an LLM that was already produced by an LLMs, the standard relationship between compression and decompression in information technology is reversed. Normally, the goal of information transmission is to keep the redundancy of a message as high as necessary in view of potential noise sources, but at the same time as low as possible in view of limited channel capacities. In the case of highly redundant natural language, compression is possible for transmission over a channel, followed by decompression at the receiver side (>-<). In the case of the “textpocalypse” mentioned above, however, the reverse happens: The message would go and come out compressed on both the sender and receiver sides, and the decompression would become the channel’s transmission codec (<=>).

In this case, LLMs are more than just simple writing aids. Rather, as one could say with Arnold Gehlen, Walter Benjamin, and Hans Blumenberg, they are tools for the psychosensory unburdening from the textual-absolute. There is evidence that that this observation is not entirely fanciful. Commercial programs such as the current Microsoft Office suite allow one to formulate entire e-mails from a series of keywords, while summarizing received messages in keyword form in turn. Elaboration is an interface between machines, not between humans, who receive only the reduced version of a text. Similarly, in the text-to-image AI DALL-E, the user’s input is no longer sent directly to the image generator, but is first embellished and provided with more details by the system. According to the OpenAI engineers, such an ornatus leads to better results, but remains largely invisible to the user. This would reformulate the aperçu of programmer Andrej Karpathy, who emphasizes the new power of natural language (“the hottest new programming language is English“), thusly: “the hottest new transmission protocol is verbose English”. Rhetoric resides not only in the message, but also in the codec.

The Facilitation of Writing

Second, as mentioned before, the facilitation of reading already plays a role in the facilitation of writing. But AI-generated abstracts are just one example of those genres that could be called texts without jouissance and that seem to be especially suitable for AI writing assistance.

For LLMs’ big promise is this: to outsource the false writing time that is wasted on quality of life-spoiling routines such as proposals, administrative communication, and final reports to the machine in order to give research more real writing time. The fact that the DFG – the German NEH – now explicitly allows this, as long as the use of generative AI is identified, is surely not least due to the realization that more and more researchers’ lives are squandered on an œuvre cachée of rejected proposals that no academic audience every gets to see.

However, the distinction between false and real writing time may be misleading when “real” writing is also done without pleasure. It might therefore be more interesting to turn to literature as a presumed case of jouissance-filled text production. The writer Jenifer Becker described her initial working mode with GPT-3 as a collective brainstorming, similar to the “writers’ room” in television series, in which ideas can be spitballed, taken up and discarded. Author Juan S. Guse recounts how he came to a similar assessment in two steps: While he initially used ChatGPT for a “collaboration ex negativo” in order to avoid “stochastically well-trodden paths”—if the AI has the same thought as me, the thought is bad—his practice has become more “maieutic” in that he now also accepts the program’s suggestions positively. 4

But these practices still seem to be about generating ideas, not literary texts. The latter is currently most likely to be produces in digital literature, which is particularly open to writing processes that exist at a certain distance from the author and at the same time do not have to follow conventional genre conventions.5 My novel (Berlin, Miami)—which I created using open LLMs called GPT-J and GPT-NeoX that I fine-tuned on contemporary literature—also belongs to this genre.6 The text was not the result of a prompt (“Write me a novel!”), but came about through repeated sentence completion.

In order to find out whether and in what way such a model is capable of narration, I intervened as little as possible and often simply let it run its course. The writing was therefore a particularly distanced affair. Nevertheless, I did not experience the LLM as an agent. Rather, I had the impression that it was the text that wanted something and was pushing in a certain direction. One is surfing on ideas, but they regularly end up absurd or digressive. For this reason, I actively intervened at some points, picking up lost leads or introducing new topics—often with just one word—that I wanted to know more about. For example, I came across the “Jawling”, invented by the model and only vaguely described, which, together with the equally vague “Pondhead”, was up to much mischief. Or I learned about the process of “diagonalization” to which the city of Miami, suffering from acute urban decay, was subjected under the aegis of the Ãää agency.

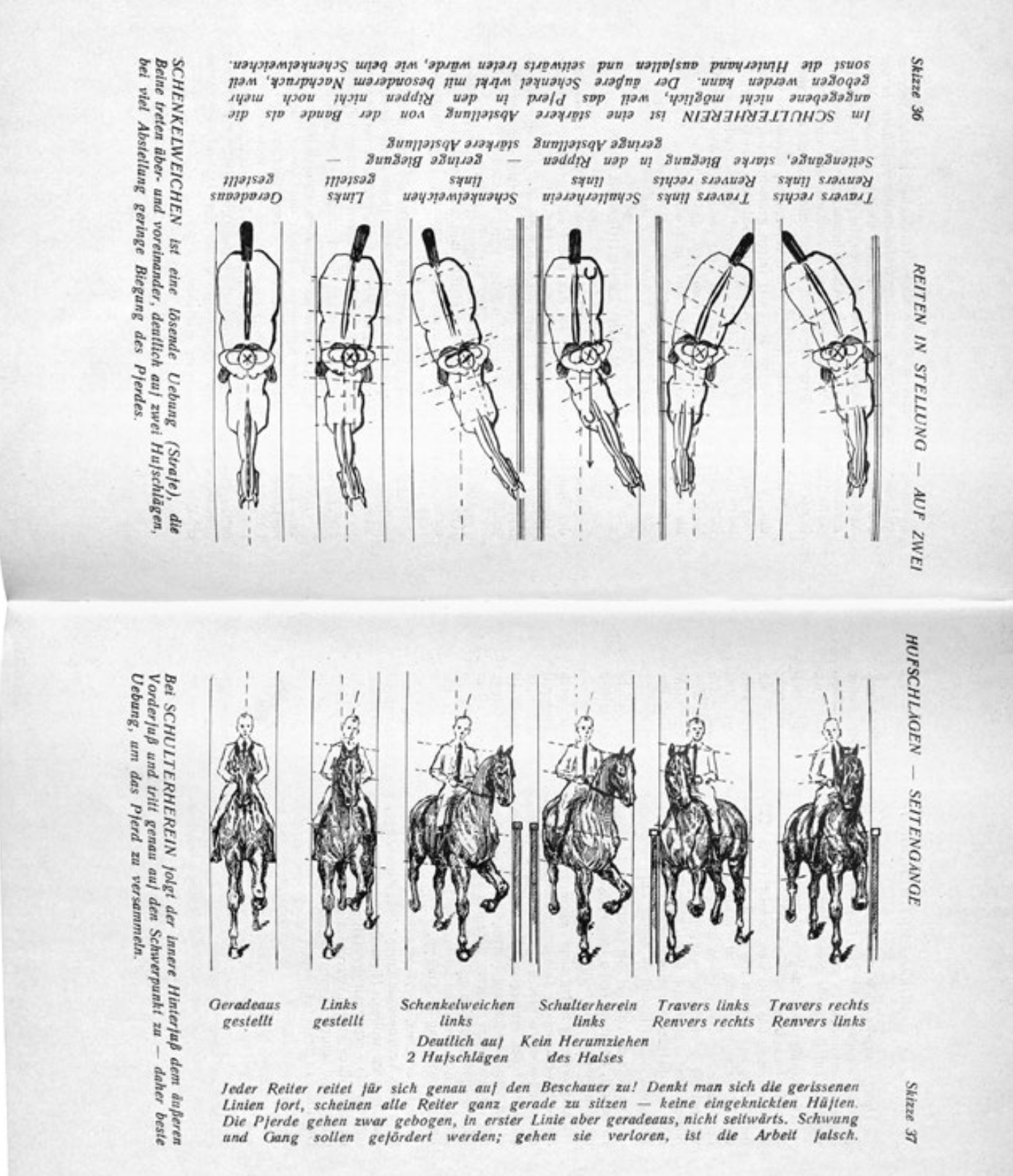

This was all so interesting that I occasionally followed up when these topics threatened to disappear, but always remaining open to what else was there to come. The writing activity then consisted mainly of alternating between surfing and small nudges—what in horseback riding is called “leg aids,” of which there are, among others, “leading” and “correcting” variants. 7 The experience of writing with AI moves between these metaphors: surfing and riding—at least for me, at least for the moment. Here, the distinction between tool and agent becomes blurred. Just as a surfboard, no matter how much you experience it as an outgrowth of your own body, is not yet an agent, it would be wrong to speak of a horse as a tool. 8 In the end, LLMs may be a third thing for which we still have to find a practice and a name.

- Moritz Hiller, “Es gibt keine Sprachmodelle,” in: Davide Giuriato, Claas Morgenroth, and Sandro Zanetti (eds.), Noten zum “Schreiben” (Paderborn: Fink, 2023), 280; see also Hannes Bajohr and Moritz Hiller, Das Subjekt des Schreibens (Munich: edition text+kritik, 2024).

- Arno Schmidt, “Julianische Tage,” in: Bargfelder Ausgabe, Werkgruppe 3: Essays und Biographisches, vol 4: Essays und Aufsätze II (Zürich: Haffmanns, 1995), 87–92.

- A study from earlier this year showed how realistic Kirschenbaum’s prediction is: the phrase “to delve into,” one of ChatGPT’s favorite phrases, now appears 10 to 100 times more often in PubMed articles than it did ten years ago.

- Juan S. Guse, “Das kombinatorische Seekuh-Prinzip.” In Schreiben nach KI, edited by Hannes Bajohr and Ann Cotten (Berlin: Rohstoff, forthcoming).

- Simon Roloff and Hannes Bajohr. Digitale Literatur zur Einführung (Hamburg: Junius 2024; Hannes Bajohr, “Writing at a Distance: Notes on Authorship and Artificial Intelligence.” German Studies Review 47, no. 2 (2024): 315–337.

- An English-language excerpt appeared in Ensemble Park with an interview about the production in the print version.

- I am not sure if I am translating this right. In German, the word is “Schenkelhilfe” and it exists in a “vorwärtstreibende,” “verwahrende,” and even vorwärts-seitwärtstreibende variant, which might indicate an especially open-ended process. See Deutsche Reiterliche Vereinigung, ed. Richtlinien für Reiten und Fahren, vol. 1, Grundausbildung für Reiter und Pferd (Warendorf: Deutsche Reiterliche Vereinigung, 2014), 83.

- At least this is how I imagine it; I can neither surf nor ride horses.

Leave a Reply