This is a rough translation of the introduction to the collected volume Das Subjekt des Schreibens: Über Große Sprachmodelle [The Subject of Writing: On Large Language Models, see also here], edited by Hannes Bajohr and Moritz Hiller, Munich 2024. The basic premises of the volume are laid out here, namely, first, that the double standard assumption that has determined our thinking about writing practices up to now—that everything written is first read as human-made, and that our so-called writing tools are always only passive devices— is up for discussion in view of the current large language models; and, second, that the status of the ‘writing subject’—a place in historically situated structures of writing that have been occupied differently at different times—must be rethought as hybrid constellations of distributed human-machine authorship. It is, in short, about the ‘scene of writing’ of large language models.

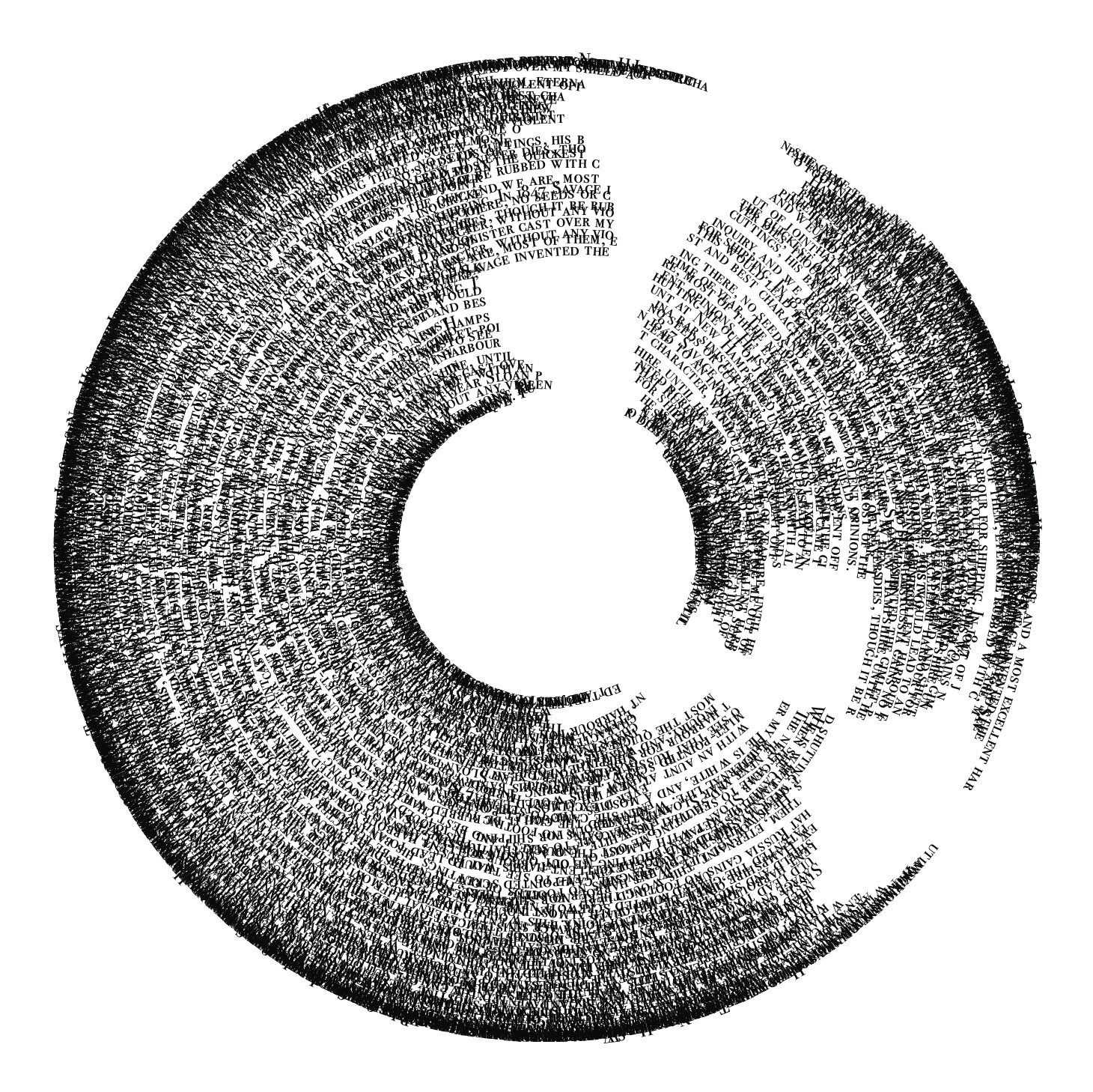

Image courtesy of Sean Cearly/futureanachronism.com

In January 2023, what is believed to be the first scientific article to attribute authorship to a so-called ‘large language model’ was published: In the pages of a journal owned by one of the world’s largest scientific publishers, the name of a computer program appears alongside the that of the human author.1

Both the human and the authorial program are explicitly identified as author. But just a few weeks later, a correction follows:

The first author became aware that the second listed author, ‘ChatGPT’, does not qualify for authorship according to the journal’s guide for authors and to Elsevier’s Publishing Ethics Policies.

‘ChatGPT’ is, therefore, removed from the author list and is acknowledged as making a substantial contribution to the writing of the paper. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

The journal and the author would like to apologize for any inconvenience caused.2

And so the name of the language model simply disappears again from the place that regulates authorship. But even if things have been brought into legally safe waters as quickly as possible: the confusion remains. The second author—the program—is not qualified to be awarded the status of authorship, it is said, even though he or she is acknowledged to have made a substantial contribution to the writing of the text. But what is a substantial contribution? And how much substance did the human author contribute?

Text productions and semiotic processes involving software such as ChatGPT at a very basic level pose the question of who—or what—writes. Since 1800, our thinking about writing, its practices, products and subjects, has been largely determined by two complementary standard expectations: Anyone confronted with an unknown text assumes, first, that what is written is to be read as human-made;3 and, second, that the writing instrument used only ever acts as a passive device.4 The emergence of contemporary large language models not only makes this standard clearly visible as a standard for the first time, since with them, for the first time there is a serious alternative to this standard. But it is also immediately up for discussion again, because a doubt has now been introduced that no assurance, however sincere, is able to dispel. The bizarre episode of authorship attribution illustrates this despite or precisely because of its hasty correction: no retraction can remedy the “inconveniences” caused by language models in the field of writing—the question of whether a text was written by a machine is now in the world and will not disappear from it.

That systems of automated text synthesis could ever achieve a degree of linguistic competence that would make them contenders for the position of author was, of course, not a given. Despite Warren Weaver’s hope, formulated in 1949, that automatic translation—and thus text production itself—could be understood as a problem of cryptography, which the young computer science would be particularly suited to solving, the connection between language and computer science has historically proved to be extremely complex.5 Homonymy, conversational implicatures, context-dependent understanding soon proved to be almost insurmountable obstacles that characterized the use of language not as automatable rule-following, but rather as the expression of a complex world-knowledge, as paradigmatically formulated by the philosophical critiques of Yehoshua Bar-Hillel, Hubert Dreyfus and John Haugeland. From this perspective, the processing of natural language is not merely the processing of information, but presupposes actual intelligence, be it linked to intention, embodied cognition or “being-in-a-situation”, which Turing machines inherently lack.6

This way of looking at the problem seemed plausible until a few years ago, when recurrent neural networks, known since the 1990s and now combined with better computing power and larger data sets, began to stir up new hopes in the long-stagnating field of natural language processing through the vectorization of word semantics.7 Since the attention mechanism was introduced in 2016, which allows to process longer context and reference dependencies and which took on its current form in 2017 in the Transformer model, still used today in ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini,8 things have begun to look different. A series of innovations—including in-context learning, instruction tuning and reinforcement learning from human feedback9—have also led to increased uncertainty about whether ‘real’ intelligence is actually necessary to generate a level of language competence comparable to that of humans; the accelerated technical development and higher output quality have done their part, too. As a result and at least at the phenomenal level, to use Max Bense’s term, in many cases today a “synthetic” text can no longer be distinguished from a “natural” text.10

Reactions to this situation range from enthusiastic invocations of the unprecedented to (self-)mollifying assurances that everything will actually remain the same. If the hope for the imminent arrival of artificial general intelligenceis now characterized by the—equally marketable—fear of its almost nuclear risks, especially in computer science and the tech industry,11 linguistics, philosophy, and literary and media studies have in large parts adopted a more defensive stance: The insistence that a large language model is “haphazardly stitching together sequences of linguistic forms it has observed in its vast training data, according to probabilistic information about how they combine, but without any reference to meaning,” that is, nothing but a “stochastic parrot”,12 again equates the capacity for written linguistic competence with a notion of subjectivity, which is precisely that of human beings. Authorship is thus human from the outset, insofar as people, and only people, become the source, but also the standard of language use. The emergence of other sources and standards of language must then automatically be considered illegitimate.13 But even if large language models have no intentions, no world model, no embodied intelligence, these observations, which are certainly correct, fail to address the fact that what they produce is, without a doubt, writing.14

This suggests a shift in the question. Instead of deciding in favor of one side or the other, in this moment of historical uncertainty or, to put it more neutrally, openness, the question of the subject of writing should be posed anew. On the one hand, it must be a matter of reflecting on the place of the human (or humans) in hybrid constellations of distributed text production, and on the other, we need at least to think about considering machines themselves, which until now have only enjoyed the status of mere instruments, as subjects of writing. It should be noted that this rephrased question intentionally makes no reference to any conscious performance on the part of machines, which should be decoupled from the concept of the subject here. When we speak of the ‘subject of writing’, we are merely proposing a conceptual alternative that, on the one hand, transcends the merely causal, instrumental character of the production of writing and, on the other, undercuts the idealistic, romantic character of authorship as an expression and arena of spirit.

Understood in this way, the subject of writing is nothing more or less than a place in historically situated structures, which, only temporarily and locally stable, each instantiate the complex process that is called writing in a specific way—be it around 1600, 1800 or at the beginning of the 21st century. This raises the question of how this place is occupied. In order to be able to deal appropriately with a currently open situation of writing, it seems advisable not to always model the place of the subject according to what has occupied it unquestioningly and exclusively for a good 200 years, ever since man, that is, was enthroned as the (one) subject of writing within the romantic concept of authorship.15

It cannot be denied that this historical occupation will have been epochal, that it has decisively determined and continues to determine our ideas of writing, authorship, and being a subject (all of which are of the same origin around 1800). The only assertion to be made here is that the situation in the time of large language models is different. Who or what can or may, should or must occupy the place of the subject under current technical, political and literary-historical conditions is therefore the question addressed in the contributions to this special volume.

For historical structures of writing, Rüdiger Campe has brought the concept of the ‘scene of writing’ into play.16 Precisely by deliberately refraining from providing a comprehensive theory of writing or only of the scene of writing, Campe’s concept gives literary research, which to date has been almost exclusively oriented towards (in the broadest sense) linguistic aspects of writing, reasons to expand its access to its subject matter to include insights into its specific technical and physical conditions from case to case. Writing, beyond the semantic, always includes a “repertoire of gestures and provisional arrangements”, which the concept of the writing scene triangulates in a given “framing” without self-evidence, as a “non-stable ensemble of language, instrumentality, and gesture”.17 This ensemble might take the place of the concept of authorship.18 Precisely when the concept, matter, and practice of writing constantly undermine their apparent immediacy, indubitability, and stability, but in different ways depending on the structure, it is “worthwhile to describe the formation of ensembles and processes of framing in their limited validity and with all their fissures”.19

To this end, Campe’s (sometimes only implicit and implied) impact has been systematized and specified by what is called ‘writing process research’ (Schreibprozessforschung). According to this field, scenes of writing are each singular and always provided with a historical index, which makes them legible as symptoms of a peculiar media situation. If different media-historical situations are characterized by different instruments of writing—handwriting, typewriter, computer—this constitutes specific scenes of writing, the effects of which exceed the local framework of a particular writing structure.20

In the field of writing under the conditions of the digital computer in particular, it is true that “concepts such as author and work or text, phase divisions such as production, distribution and reception of writings (or codes?) and instances of evaluation, regulation and exercise of power […] would not disappear from the discourse”:

But their specific order cannot simply be assumed (e.g. as centrally, hierarchically and meaningfully organized), but can only be determined—also as disorder or rearrangement—from the equally specific media dispositif in which it is formed, transformed or deformed. […] Only then can the writing and reading processes that take place in such a dispositif be determined more precisely and the traditions in which they stand—or do not stand—be named.21

Where the double standard assumption that has determined our approach to writing and writing since 1800—that texts are always of human origin and the devices of passive instrumentality—is currently losing its validity, this special issue merely assumes that a “specific order” has once again been set in motion with machines such as ChatGPT. The contributions collected here therefore provide approaches to reconstructing what Campe might call the ‘LLMs’ scene of writing’.22 The methodological distinction of writing process research, which separates the semantics, technology and physicality of writing, only needs to be extended to include the aspect of its subject.

For such attempts at reconstruction, as past and current discussions in the field of artificial intelligence leave little doubt, it will be all too tempting to think of the possible subject status of language models, which are no longer passive instruments, as analogous to the model of human authorship. What once characterized humans—consciousness, experience, creativity—is then simply transferred to machines. And in view of the widespread affinity for simple symmetries (or dystopias such as a technological singularity), it can be assumed that humans themselves are assigned a corresponding place among the mere (subjugated) instruments. However, such a simple role reversal between man and machine, previous subjects and instruments, would be analytically unsatisfactory, as it would maintain the very separation on which the stable and humanistic-programmatic standard assumption of writing is based—and which, according to the thesis of this special volume, is becoming questionable with the current language models.

Abandoning the previous standard assumption about subject and device without at the same time replacing it with its simple inversion therefore seems essential for an inventory of AI scenes of writing. After all, in view of the production of writing that takes place with the participation of language models, no one should deny that humans can continue to participate in it and—in concrete situations to be described—do participate: They provide (mostly unconsciously and unsolicited) training data, implement neural networks and initiate the calculation of statistical distributions, they formulate prompts and edit machine outputs which, once published, will serve as training data for the next model iteration.23

The schematic list of writing practices that humans perform in the age of large language models (for the moment still) thus completes a cycle that undoubtedly makes all those who are involved in it subjects of writing. But in view of this cycle—which contains all kinds of practices that would generally be categorized as ‘writing’, but not what was called ‘writing’ in the emphatic sense—no one should deny that people no longer play the same role in such writing scenes as was intended for them by concepts of authorship and subject philosophies for the longest time and as still determines our everyday understanding of romantic, legal, or merely causal authorship today.

In the age of large language models, the place of the writing subject is differently occupied. What takes this place is no longer (only) ‘The Human’ nor ‘The Machine,’ but possibly a heterogeneous figuration whose name has yet to be found and which—without falling prey to transhumanist fantasies or other ideologemes of the tech industry24—would have to ensure that, in the long term, the thinking of this place and its occupation is freed from the legacy of the simple dichotomy of human and machine. If writing is no longer exclusively associated with a human subject, but machines are also assigned a subjecthood of writing that is not always modeled on the model of (human) authorship, this obviously touches on elementary categories of literary, media, and cultural studies. Is there a need, we might ask, to fundamentally revise some of its established assumptions, concepts and models? Do others—think of the postulates and programs of so-called post-structuralism—only reveal themselves to be fully applicable in this historical situation? Or are they too still imbued with assumptions that prove to be too abstract when confronted with the reality of large language models?

This special volume brings together positions that approach the question of the subject of writing from different perspectives. This includes fundamental reflections of a theoretical nature—on writing processes, notions of texts, and concepts of authorship—as well as prehistories of neural networks and learning machines; media archaeologies of actual language models; the analysis of their products, policies, techniques, and aesthetics; anthropologies of their practices; the economic status of their agents; and, last but not least, considerations of the place of the reader.

The volume is divided into four parts. In the first part, the contributors deal with the question of what the subject of writing is and could be and what problems arise from this reformulation in the era of large language models. In his contribution, which directly follows on from writing scene research, Sandro Zanetti proposes that the writing subject in the age of large language models should be understood as interactions between human and machine actors. The central role here is played by the simultaneous and reciprocal interlocking of different automatisms—psychological, physical, technical, and cultural—which interact with each other in the writing process and influence each other at their interfaces. Where Zanetti ultimately hesitates to grant language models their own subject position, Leif Weatherby argues against the “residual humanism” of a hierarchization of human and machine generation of meaning and for a complex understanding of the dynamic semiotic interactions between them, with the figure of thought of an ‘autonomy of the symbolic order’ located between structuralism and post-structuralism. Gabriele Gramelsberger sees a radically shifted subjectivity of writing in the digital present, which is triggered by the growing agency and authority of algorithms: Control over the interpretation of data and information is increasingly being transferred to machines, turning people into objects of digital inscriptions and behavioral conditioning. For Bernhard J. Dotzler, this “fourth insult” to humanity by artificial intelligence is in continuity with the cybernetic criticism against overestimating the supposed sovereignty of the subject, whereby conversely, the exaggeration of the machine as a meaning-producing entity is merely a projection. Finally, Mercedes Bunz argues with Jacques Derrida, André Leroi-Gourhan, and Gilbert Simondon that the generative writing of language models can no longer be understood as an exteriorization of human subjectivity, but is a new way of producing meaning that can best be addressed with an expanded literary theory.

The second part focuses on historical analyses of the concrete ensemble formations before and in large language models. Markus Krajewski approaches the prehistory of artificial intelligence by placing it in the lineage of intellectual furniture dating back to the Baroque era, which has always characterized writing activity as outsourced and collaborative, from the writing desk to the card index. In this respect, the mind is not in the head, as Christina Vagt shows with a look at the history and theory of neural networks, which have always served as a model of human cognition since their formalization by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts in 1943. As this historical review shows, thinking itself is always constructed by media. However, Anna Tuschling argues that the subject of writing cannot be understood solely as a collaboration between human and machine actors. Drawing on the complicated history of machine translation, she shows how economic, socio-political and academic competition, and ultimately a structural competition inherent in language itself, constitute the writing subject.

The third part deals with specific literary authorship that is challenged by the developments of artificial intelligence. In a thought experiment, Kurt Beals addresses the all-too-smooth declarations of the authorial figure’s obsolescence, which has always been attributed to post-structuralism: If Kafka’s work had not been written by Kafka himself, but by an artificial intelligence, would we really read his texts in the same way? According to Beals, the phenomenon of ‘mistakes’ in such a work would have a radically different meaning—in one case it would be something that needs to be explained, in the other it would be a rejection to be ignored. Leah Henrickson, on the other hand, argues that the relevance of a literary text is not a question of its origin. Insofar as texts invoke a ‘hermeneutic contract’, they are no guarantee of authenticity, but merely catalysts for reflection on the part of those who read them. The fact that something radically new has come into the world with large language models, which classical authorship theories cannot capture, is what Matthew G. Kirschenbaum means when he describes the changes in the writing scene in the mass production of writing as a “textpocalypse”, in which synthetic texts threaten to flood our writing ecologies. And by turning to concrete examples of literary works generated with the help of artificial intelligence, Stephanie Catani shows that the renegotiation of authorship is taking place above all where the fiction of the identity of author and narrator is operative in the genres of autofiction and autobiography.

The volume concludes with the fourth part, which contains observations on the finding that the text production of contemporary language models cannot be detached from social, political and economic processes, which themselves represent strategies of subjectivation. Sarah Pourciau and Tobias Wilke focus on the coding of femininity as an “undifferentiated category of an analogous real” that has always represented thinking in artificial intelligence, drawing a historical line from Alan Turing’s imitation gameto Max Bense’s and Ludwig Harig’s “Monologue of Terry Jo” to Spike Jonze’s “Her,” and finally the most recent language model GPT-4o. Alexander R. Galloway‘s contribution reflects on the hegemony of an empirical scientific methodology inscribed in the principle of machine learning, its theatricality of truth, and the embedding of cultural and social values in the training data of the models. Insofar as they are based on the expropriation of data from the commons, they represent a kind of Marxian “original accumulation” that makes their socialization politically desirable. In the final contribution to this volume, Hito Steyerl also turns to this accumulation, which is particularly evident in the combination of artificial intelligence and crypto-fintech. She contrasts the attempt to automate human common sense via poorly paid clickworkers with Antonio Gramsci’s concept of the senso comune as a political resource that could be used to reclaim the commons. At this point of the political, which is always already embedded in the technical, the assumed subject status of machines may then find its limit.

Hannes Bajohr / Moritz Hiller

- O’Connor, Siobhan. “Open Artificial Intelligence Platforms in Nursing Education: Tools for Academic Progress or Abuse?” Nurse Education in Practice 66 (2023): 103537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103537.

- O’Connor, Siobhan. “Corrigendum to ‘Open Artificial Intelligence Platforms in Nursing Education: Tools for Academic Progress or Abuse?’ [Nurse Educ. Pract. 66 (2023) 103537].” Nurse Education in Practice 67 (2023): 103572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103537.

- Bajohr, Hannes. 2024. “On Artificial and Post-Artificial Texts: Machine Learning and the Reader’s Expectations of Literary and Non-Literary Writing.” Poetics Today 45 (2): 331–61, https://doi.org/10.1215/03335372-11092990. Although the assumption of a human origin usually also implies a consciously intended communication of meaning—a human being wants to say something—there have always been exceptions to this, from trance experiences to écriture automatique, while the human origin itself was not in doubt. Even religious texts are no exception here, since—apart perhaps from the tablets of the law of Moses—they were still the product of human scribes, even if their wording may have originated from higher powers.

- Hiller, Moritz. “Es gibt keine Sprachmodelle.” In Noten zum “Schreiben,” edited by Davide Giuriato, Claas Morgenroth, and Sandro Zanetti, 279-285. Paderborn, 2023.

- Weaver, Warren. “Translation.” In Readings in Machine Translation, edited by Sergei Nirenburg, Harold L. Somers, and Yorick Wilks, 13-17. Cambridge, MA: 2003.

- Bar-Hillel, Yehoshua. “The Present State of Research on Mechanical Translation.” American Documentation 4, no. 2 (1951): 229-237; Dreyfus, Hubert L. What Computers Can’t Do: A Critique of Artificial Reason. New York, 1972; Haugeland, John. Artificial Intelligence: The Very Idea. Cambridge, MA, 1989. Haugeland and, less directly, Dreyfus are currently followed most prominently by Brian Cantwell Smith, who contrasts the machine calculation of formal calculations called reckoning with the power of judgment that presupposes knowledge of the world: Smith, Brian Cantwell: The Promise of Artificial Intelligence. Reckoning and Judgment, Cambridge, MA, 2019.

- Two works are particularly important here: Mikolov, Tomas, et al. “Distributed Representations of Words and Phrases and Their Compositionality.” In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 3111-3119. Red Hook, 2013; Sutskever, Ilya, Oriol Vinyals, and Quoc V. Le. “Sequence to Sequence Learning with Neural Networks.” arXiv, December 14, 2014. https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.3215. In 2015, Andrej Karpathy wrote an influential, practically oriented blog entry about the “unreasonable effectiveness” of this technology, which, together with the code repository linked in it, contributed a great deal to its popularization, Karpathy, Andrej. “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Recurrent Neural Networks.” May 21, 2015. https://karpathy.github.io/2015/05/21/rnn-effectiveness.

- Bahdanau, Dzmitry, et al. “Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate.” arXiv, May 19, 2016. https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.0473; Vaswani, Ashish, et al. “Attention Is All You Need.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (2017): 5998-6008.

- Brown, Tom B., et al. “Language Models are Few-Shot Learners.” arXiv, May 28, 2020. http://arxiv.org/abs/2005.14165; Ouyang, Long, et al. “Training Language Models to Follow Instructions with Human Feedback.” arXiv, March 4, 2022. http://arxiv.org/2203.02155.

- Bense, Max. “Über natürliche und künstliche Poesie.” In Theorie der Texte: Eine Einführung in neuere Auffassungen und Methoden, 143-147. Köln, 1962; an English translation can be found here: https://hannesbajohr.de/en/2023/03/13/max-bense-on-natural-and-artificial-poetry-1962/

- Bubeck, Sébastien, et al. “Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early Experiments with GPT-4.” arXiv, March 13, 2023. https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.12712; Yudkowsky, Eliezer. “The Open Letter on AI Doesn’t Go Far Enough: We Need to Shut It All Down.” Time, March 29, 2023. https://time.com/6266923/ai-eliezer-yudkowsky-open-letter-not-enough

- ; Bender, Emily M., Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” In FAccT ’21: Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 610–23. Association for Computing Machinery, 2021; see for an analysis of the rhetoric that equates AI with the A-Bomb: Wilke, Tobias. “KI, die Bombe: Zur Gegenwart und Geschichte einer Analogie.” ZfL-Blog, October 19, 2023. https://www.zflprojekte.de/zfl-blog/2023/10/19/tobias-wilke-ki-die-bombe-zu-gegenwart-und-geschichte-einer-analogie.

- Such is the argument in: Van Woudenberg, René, Chris Ranalli, and Daniel Bracker. “Authorship and ChatGPT: A Conservative View.” Philosophy & Technology 34, no. 37 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-024-00715-1.

- See Hiller, “Es gibt keine Sprachmodelle.”

- Bosse, Heinrich. Autorschaft ist Werkherrschaft: Über die Entstehung des Urheberrechts aus dem Geist der Goethezeit. Paderborn, 1981; Woodmansee, Martha. “The Genius and the Copyright: Economic and Legal Conditions of the Emergence of the ‘Author.’” Eighteenth-Century Studies 17, no. 4 (1984): 425-448.

- Campe. “Writing; The Scene of Writing.” MLN 136, no. 5 (2021): 971–83. https://doi.org/10.1353/mln.2021.0075.

- Campe, “Writing,” 973.

- Campe, Rüdiger. “Writing Scenes and the Scene of Writing: A Postscript.” MLN 136, no. 5 (2021): 1114-1133. https://doi.org/10.1353/mln.2021.0082

- Campe, “Writing,” 973.

- Stingelin, Martin, ed. (in collaboration with Davide Giuriato and Sandro Zanetti). “Mir ekelt vor diesem tintenklecksenden Säkulum”: Schreibszenen im Zeitalter der Manuskripte. Munich, 2004; Giuriato, Davide, Martin Stingelin, and Sandro Zanetti, eds. “SCHREIBKUGEL IST EIN DING GLEICH MIR: VON EISEN”: Schreibszenen im Zeitalter der Typoskripte. Munich, 2005; Giuriato, Davide, Martin Stingelin, and Sandro Zanetti, eds. “System ohne General”: Schreibszenen im digitalen Zeitalter. Munich, 2006.

- Zanetti, Sandro. “(Digitalisiertes) Schreiben: Einleitung.” In “System ohne General”: Schreibszenen im digitalen Zeitalter, edited by Davide Giuriato, Martin Stingelin, and Sandro Zanetti, 717, Munich, 2006.

- Eva Geulen recently commented on the scene of writing in the age of artificial intelligence: Geulen, Eva. “Schreibszene: Fanfiction (mit einer Fallstudie zu Joshua Groß).” In Wie postdigital schreiben? Neue Verfahren der Gegenwartsliteratur, edited by Hanna Hamel and Eva Stubenrauch, 51-68. Bielefeld, 2023.

- See for example the concept of “distributed authorship” in: Meerhoff, Jasmin. “Verteilung und Zerstäubung: Zur Autorschaft computergestützter Literatur.” In Digitale Literatur II, edited by Hannes Bajohr and Annette Gilbert, 49-61. Munich, 2021; and the respective section in: Bajohr, Hannes. “Writing at a Distance: Notes on Authorship and Artificial Intelligence.” German Studies Review 47, no. 2 (2024): 315-337. https://doi.org/10.1353/gsr.2024.a927862.

- Gebru, Timnit, and Émile P. Torres. “The TESCREAL Bundle: Eugenics and the Promise of Utopia Through Artificial General Intelligence.” First Monday 29, no. 4 (2024). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v29i4.13636.

Leave a Reply